By Abel Rodríguez, JD ('01), Assistant Professor of Religion, Law, and Social Justice

Originally published in October 2016, in the Fall 2016 Cabrini Magazine

Immigration has been among the most contentious issues in the national discourse throughout this country’s history, from the race-based citizenship and exclusion laws of the first half of the 20th century to the raids and mass deportations of migrant workers that persist today.

With the impending presidential elections, immigration has again risen to the forefront of the collective American consciousness. Predictably, the political rhetoric continues to overlook the root causes of migration, and justice for our immigrant communities remains elusive. The dominant political discourse continues to conflate migration with criminality as politicians threaten to build literal and metaphorical walls, as well as exclude individuals on the basis of religious affiliation.

This year, coincidentally, also marks the 70th anniversary of the canonization of Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini, the Patroness of Immigrants. In her tireless work with the Italian immigrant community, Mother Cabrini was cognizant of the negative perceptions many people in the United States held against newcomers to this country. She encountered active resistance to her work, including resistance from some of her own coreligionists. In turn, Mother Cabrini set out to demonstrate that “Italian immigration is not a dangerous element” to this country. As former Cabrini President Mary Louise Sullivan, MSC, has rightly argued, Mother Cabrini would “deplore [the] renascent xenophobia” currently espoused. The Patroness of Immigrants would “advocate an appreciation of the cultural values and heritage of newcomers.” Nonetheless, the fear of “the Other,” confronted by Mother Cabrini, endures today.

Amidst the current hostility, I have designed my classes to mesh the school’s mission and Mother Cabrini’s intentions with pressing contemporary moral issues regarding migration. In my Engagements with the Common Good (ECG) course titled Immigration, Law, and Social Justice, students learn about the U.S. immigration legal system and analyze its effects on people in migration through the lens of Catholic social teaching. Students work alongside immigration advocates in the Philadelphia area interpreting at legal clinics, assisting attorneys providing free services to clients pursuing citizenship, and conducting research to support clients facing deportation proceedings in immigration court.

Their direct service work, in the spirit of Mother Cabrini, is complemented by reflection expressed, in part, through creative projects that bring to light the social injustices faced in the current climate of anti-migrant sentiment.

The Injustice of Deportation and Detention

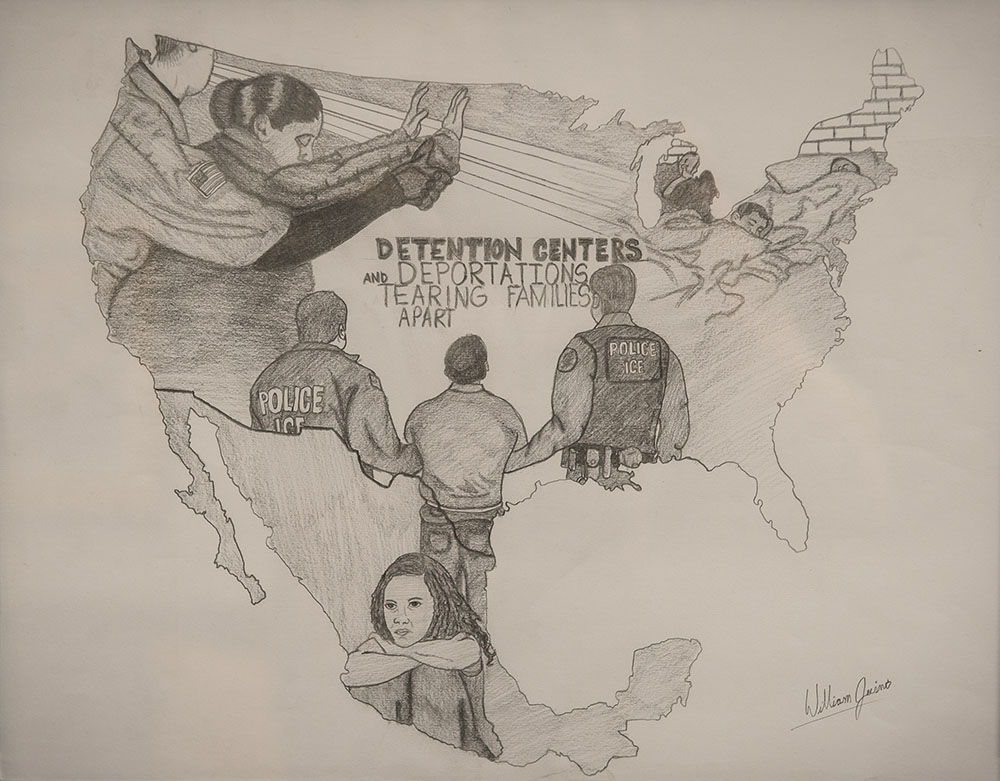

The depth of reflection in many of my students’ creative projects has been remarkable, insightfully addressing the implications of laws and policies that exacerbate global inequality and institutionalize violence against people in migration. For example, in his sketch titled “Detention Centers and Deportations: Tearing Families Apart,” student William Jusino (’18) adeptly depicts the separation of families that occurs both within our borders and abroad. The result of economic policies pushing parents into migration for employment, a young girl remains alone in Mexico. Within our borders, children sleep while their parents face violent apprehension. The beam of light that emanates in their direction alludes to the early morning raids targeting mothers and children from Central America. The bricks remind us of the children currently confined behind the walls of immigration detention centers.

The circumstances William highlights are the result of an insidious system that leads to mass deportation and immigration incarceration. To date, the Obama administration has deported more than 2.5 million people, surpassing all previous administrations, and continues to allow women and children to be detained in deplorable conditions in Texas and Berks County, PA, only 50 miles from Cabrini University. President Obama has garnered support for mass deportations by assuring the public that immigration officials focus their resources on those who “pose the greatest threat to public safety.” In reality, however, the vast majority of the 300,000 to 400,000 people being deported each year pose no threat to anyone, and a growing number of deportees’ only contact with law enforcement is the result of a traffic stop.

Dehumanization at the Border

Portraying immigrants as a threat to the nation perpetuates official policies that dehumanize and degrade people in migration. Reflecting on the lives lost on our southern border, Maggie Javitt (’18) considers the effects of U.S. border policy on people fleeing violence, poverty, and disasters. Resourcefully using a Goldfish cracker box—a mainstay of undergraduate snack life—Maggie has crafted a coffin to represent the violence that occurs on the U.S.-Mexico border each year. The red casket reminds us of the blood spilled by those attacked by thieves, injured hopping trains, or killed by Border Patrol agents on their journey. The feet and skulls represent, respectively, the perilous journey across multiple borders and the hundreds of lives lost each year. Written on the coffin is a collective epitaph for all who have died in migration, conveying many of the reasons that people risk their lives: for safety, for work, for family.

Notably, the coffin remains open. Maggie reminds us that current border policies, which intentionally divert people in migration to isolated portions of the desert, will continue to result in lives lost daily. According to U.S. Border Patrol’s own estimates, more than 6,000 people have died since the year 2000 on our southern border—more than one person per day. The total number of deaths undoubtedly surpasses that estimate, yet politicians on both sides of the aisle continue to call for more of the same brand of “border security.” Although many of those crossing the border are families fleeing gang violence, they face the possibility of further violence in migration, with armed Border Patrol agents using force at least 1,000 times each year. Additionally, the open coffin calls for our continued connection to those we have lost. We are urged to remember them and acknowledge that each of their lives was sacred.

Toward a More Just Future

It is important to remember that, regardless of the outcome of the upcoming elections, the injustices considered by William and Maggie will continue. Although the current major presidential candidates’ immigration platforms differ markedly, neither has vowed to decrease the number of deportations or eschew language that portrays immigrants as a threat to the nation. Both plan to continue to militarize our southern border. Undoubtedly, each candidate would continue to support economic policies and military interventions abroad that thrust people into migration. And, presumably, Congress will continue to obstruct immigration reform, let alone comprehensive reform that truly protects human rights and situates the nation in solidarity with people in migration.

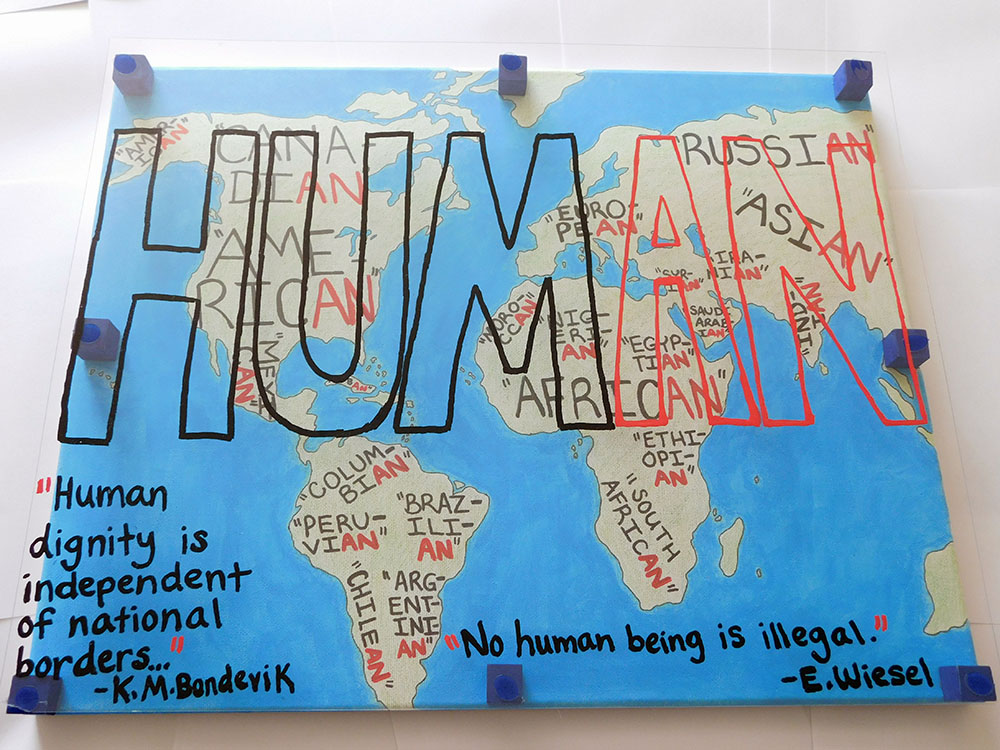

A more just immigration system must begin with a fundamental shift in the way we imagine people in migration. In her painting, student Ashley Woodruff (’19) appeals to her audience to reimagine a world that recognizes our common humanity. Although we maintain our distinct national or regional identities, that fact is overshadowed by our unity as one human family. Ashley proposes a world without borders, in which people are not constrained in their movement to find work or family and global prosperity is no longer stifled by artificial barriers. She envisions a world in which people from developing countries possess the same mobility as those from developed countries. The quotations featured prompt us to recognize that each of us, regardless of nationality or immigration status, is endowed with human dignity. Language that confuses immigration status with illegality is not only inaccurate; it also serves to degrade both the people to whom it is directed, as well as those who use such language.

Starting at Cabrini

Cabrini University remains an expression of Mother Cabrini’s profound dedication to education and service. At the end of each semester, I ask my ECG classes how, if at all, they will engage with immigration issues beyond my course. Most students state in some way they will enter into dialogue with others to reframe the narrative, disarm people of their fears, or shed light on the root causes of migration. More socially conscious students note that they also intend to engage in activism or continue to work with agencies serving immigrant communities. They have all come to the realization that—because immigrants have been and are an integral part of, rather than a threat to, this nation’s progress—they must combat such pervasive fear with informed opinion, love, and action. In today’s divisive political climate, I can think of no better way for students at the university bearing Mother Cabrini’s name to honor her vision and carry on her work.